Peter Ellerton ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

University of Queensland apporte un financement en tant que membre adhérent de The Conversation AU.

Voir les partenaires de The Conversation France

How do you know what the weather will be like tomorrow? How do you know how old the Universe is? How do you know if you are thinking rationally?

These and other questions of the “how do you know?” variety are the business of epistemology, the area of philosophy concerned with understanding the nature of knowledge and belief.

Epistemology is about understanding how we come to know that something is the case, whether it be a matter of fact such as “the Earth is warming” or a matter of value such as “people should not just be treated as means to particular ends”.

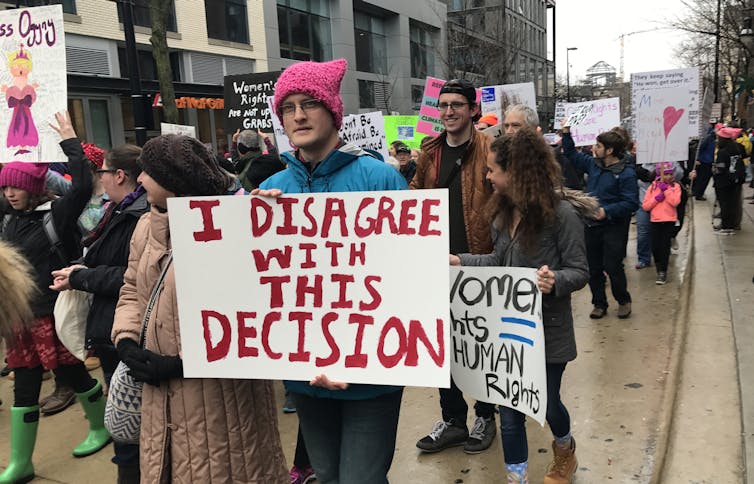

It’s even about interrogating the odd presidential tweet to determine its credibility.

Epistemology doesn’t just ask questions about what we should do to find things out; that is the task of all disciplines to some extent. For example, science, history and anthropology all have their own methods for finding things out.

Epistemology has the job of making those methods themselves the objects of study. It aims to understand how methods of inquiry can be seen as rational endeavours.

Epistemology, therefore, is concerned with the justification of knowledge claims.

Whatever the area in which we work, some people imagine that beliefs about the world are formed mechanically from straightforward reasoning, or that they pop into existence fully formed as a result of clear and distinct perceptions of the world.

But if the business of knowing things was so simple, we’d all agree on a bunch of things that we currently disagree about – such as how to treat each other, what value to place on the environment, and the optimal role of government in a society.

That we do not reach such an agreement means there is something wrong with that model of belief formation.

It is interesting that we individually tend to think of ourselves as clear thinkers and see those who disagree with us as misguided. We imagine that the impressions we have about the world come to us unsullied and unfiltered. We think we have the capacity to see things just as they really are, and that it is others who have confused perceptions.

As a result, we might think our job is simply to point out where other people have gone wrong in their thinking, rather than to engage in rational dialogue allowing for the possibility that we might actually be wrong.

But the lessons of philosophy, psychology and cognitive science teach us otherwise. The complex, organic processes that fashion and guide our reasoning are not so clinically pure.

Not only are we in the grip of a staggeringly complex array of cognitive biases and dispositions, but we are generally ignorant of their role in our thinking and decision-making.

Combine this ignorance with the conviction of our own epistemic superiority, and you can begin to see the magnitude of the problem. Appeals to “common sense” to overcome the friction of alternative views just won’t cut it.

We need, therefore, a systematic way of interrogating our own thinking, our models of rationality, and our own sense of what makes for a good reason. It can be used as a more objective standard for assessing the merit of claims made in the public arena.

This is precisely the job of epistemology.

One of the clearest ways to understand critical thinking is as applied epistemology. Issues such as the nature of logical inference, why we should accept one line of reasoning over another, and how we understand the nature of evidence and its contribution to decision making, are all decidedly epistemic concerns.

The American philosopher Harvey Siegel points out that these questions and others are essential in an education towards thinking critically.

By what criteria do we evaluate reasons? How are those criteria themselves evaluated? What is it for a belief or action to be justified? What is the relationship between justification and truth? […] these epistemological considerations are fundamental to an adequate understanding of critical thinking and should be explicitly treated in basic critical thinking courses.

To the extent that critical thinking is about analysing and evaluating methods of inquiry and assessing the credibility of resulting claims, it is an epistemic endeavour.

Engaging with deeper issues about the nature of rational persuasion can also help us to make judgements about claims even without specialist knowledge.

For example, epistemology can help clarify concepts such as “proof”, “theory”, “law” and “hypothesis” that are generally poorly understood by the general public and indeed some scientists.

In this way, epistemology serves not to adjudicate on the credibility of science, but to better understand its strengths and limitations and hence make scientific knowledge more accessible.

One of the enduring legacies of the Enlightenment, the intellectual movement that began in Europe during the 17th century, is a commitment to public reason. This was the idea that it’s not enough to state your position, you must also provide a rational case for why others should stand with you. In other words, to produce and prosecute an argument.

This commitment provides for, or at least makes possible, an objective method of assessing claims using epistemological criteria that we can all have a say in forging.

That we test each others’ thinking and collaboratively arrive at standards of epistemic credibility lifts the art of justification beyond the limitations of individual minds, and grounds it in the collective wisdom of reflective and effective communities of inquiry.

The sincerity of one’s belief, the volume or frequency with which it is stated, or assurances to “believe me” should not be rationally persuasive by themselves.

If a particular claim does not satisfy publicly agreed epistemological criteria, then it is the essence of scepticism to suspend belief. And it is the essence of gullibility to surrender to it.

There is a way to help guard against poor reasoning – ours and others’ – that draws from not only the Enlightenment but also from the long history of philosophical inquiry.

So the next time you hear a contentious claim from someone, consider how that claim can be supported if they or you were to present it to an impartial or disinterested person:

In other words, make the commitment to public reasoning. And demand of others that they do so as well, stripped of emotive terms and biased framing.

If you or they cannot provide a precise and coherent chain of reasoning, or if the reasons remain tainted with clear biases, or if you give up in frustration, it’s a pretty good sign that there are other factors in play.

It is the commitment to this epistemic process, rather than any specific outcome, that is the valid ticket onto the rational playing field.

At a time when political rhetoric is riven with irrationality, when knowledge is being seen less as a means of understanding the world and more as an encumbrance that can be pushed aside if it stands in the way of wishful thinking, and when authoritarian leaders are drawing ever larger crowds, epistemology needs to matter.